Servicing A New-To-Me 1970 Seiko 7005(A)-8020

Resurrecting a market find from Uruguay's capital.

Vintage shops and antique stores don’t line the streets of Montevideo, UY the way they do downtowns in the US, so when I arrived in one of South America’s smallest countries hoping for a thriving vintage watch scene, I came up empty.

In the States my rounds included pawn shops, jewelry stores, estate sales, and a steady stream of pieces procured online. Uruguay is a different animal. Estate sales go through auction houses, antique stores are rare, import costs are steep, and great deals are found at ‘ferias’. These open air outdoor markets serve as community meetups every week and allow a visit to your produce vendor, butcher, hardware shop, and favorite food stand in a matter of blocks. It’s a versatile place, it’s crazy as it sounds, and a quintessential Montevideo experience.

Feria Tristán Narvaja is the biggest of them. Every Sunday from early morning to mid-afternoon it iterates into its chosen weekly shape, with staple vendors anchoring a constantly shifting collection of others. I’ve found about four watch dealers there so far (if you could label them that, their stands are oft full of other tchotchkes as well), and they’re almost never in the same place.

I’ve been lucky to scoop up a few pieces that have cleaned up well, and I’ve found a few other methods of procurement in MVD that have led to some exciting watch experiences which I hope I’ll have the motivation to write about in the future. Find below my attempt at a

-inspired, semi-technical, quite informal write up of a Seiko 7005-8020 that I snagged off of a vendor at Tristán Narvaja, gave a reasonable clean up, and hope to gift to a friend for their 30th very soon.

This is how I found it, running, which for my still-fairly-novice set of watchmaker skills is my usual goal, but with some obvious work that needed to be done. It’s amazing what you can do for a watch’s curb appeal with just a crystal change, but I knew a watch made in 1970 coming from a glorified flea market was going to need a little more TLC. I could barely make out through the crystal that the dial code matched the case back, and that gave me enough confidence to move forward. I think this was a twenty dollar US purchase that day at the feria.

Getting the case apart I could take a look at what I was really working with; a pleasant surprise. The dial is in great condition given the damage to the crystal. There’s an expected amount of wear/corrosion on the indices, it’s certainly not a NOS watch, but it doesn’t seem like it’s been mismanaged too terribly considering where I came into possession of it. The wear on the hands was similar to the indices, something I prefer to mismatched wear. The crown is bent in relation to the stem, but not so much that it hinders its function or protrudes from the case abnormally in its resting position, so I decided I would just let it add a bit of character. Reworking old crowns/stems too often results in a replacement needing to be ordered. These are the types of judgement calls where I try to lean toward originality. The lume is in good shape throughout, hand lume is perfect considering age, index plots are okay, but I do see at this point in the inspection that I’m missing my six o'clock plot. Couldn’t expect it to be too perfect as a twenty dollar market find.

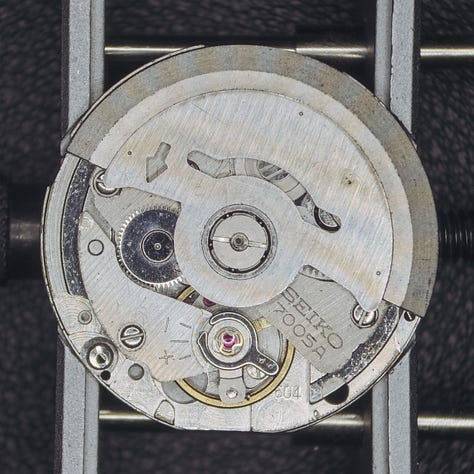

Dial goes away and we’re on to the movement. The rotor’s spinning freely, which i expected for a runner. Some preliminary timegrapher readings show within two-minute-per-day rates and a serviceable amplitude. The hairspring looks like it’s holding good shape from my initial top down. The whole thing’s a bit dingy, but I can fix that.

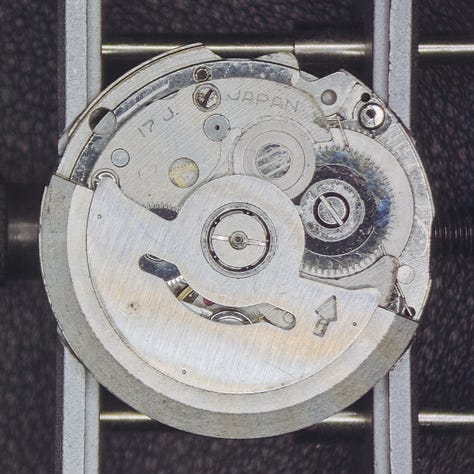

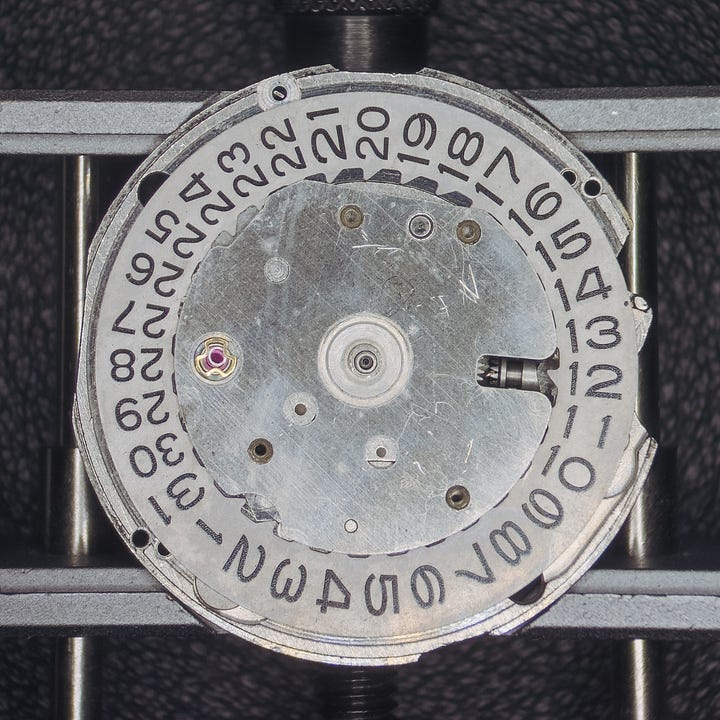

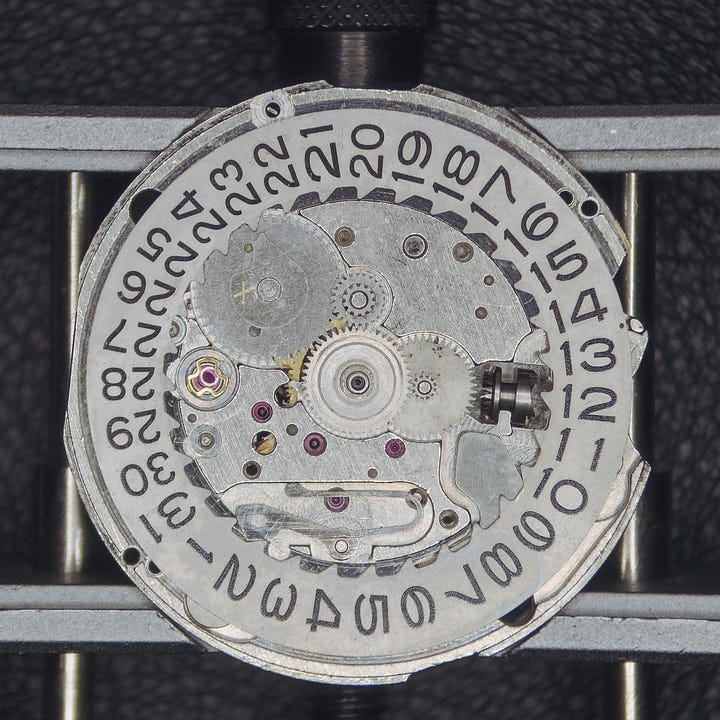

On the dial side, the calendar wheel printing is intact, another huge plus for the watch’s aesthetic count. Calendar plate comes off and we get a good view of the calendar and motion works. This date wheel spring is one I’m used to in Seiko movements, but most of the Seikos I’ve worked on have had a crown push quickset, so it took me a second to figure out the advance mechanism for the quickset on the 7005. There’s no manual winding option on this movement, so instead of a clutch on the sliding pinion where it would usually interact with a winding pinion, you have a similar shape, but those clutch-style teeth interact with the date wheel, advancing it one direction, and slipping as a clutch the other direction in the first crown position. One of the elements that I love about this movement is the all-metal date driving wheel. In my experience, Seiko likes to use plastic for the part that actually interacts with the date wheel after the intermediate. This usually doesn’t create too many problems, but I have had them come out broken before, so the 7005’s all metal version (on my example marked with an inscribed ‘X’) is a welcome choice.

The setting lever that interacts with the stem on this watch meets up with a yoke that acts as its own spring. I like this yoke/spring design. It reminds me of the long spring used for tensioning the quick setting mechanism at the top of other Seiko movements from this period, and it’s easy to remove without having to worry about the part flying off into the void. The yoke has three positions for the setting lever, resting (no function, sliding pinion turns freely), one click out (date setting function, sliding pinion interacts with date wheel), and two clicks out (time setting function, sliding pinion interacts with motion works).

The 7005 also features an interesting detent design for releasing the stem from the setting lever. In most movements you find a setting lever screw that interacts with the setting lever, or a detent button that lives between the base plate and a watchmaker-side bridge that will quick-release the stem, but this detent lives in the base plate with a tensioned cylinder that feature two cuts for removal.

Last item of note on this side is one half of the single pair of diashock jewel settings for the balance wheel.

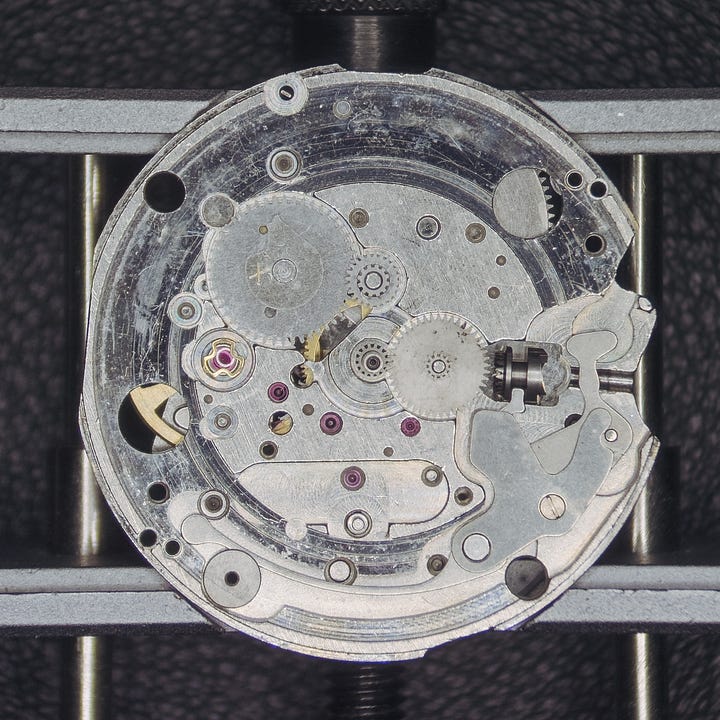

My usual order of disassembly for the balance side of the movement is balance assembly > pallet fork > gear train up to barrel. The 7005 has an abnormal automatic winding works assembly though that is part of the main gear train bridge. I wasn’t super familiar with what I was working with, so to try and negate damage to any parts I wasn’t aware of yet, I decided to start with the magic lever implementation. I removed the reverse-thread-held transmission wheel that the magic lever itself interacts with, and carefully lifted the pawl arms out of the way. I then let all of the power out of the mainspring, and removed the train wheel bridge. You can see the magic lever assembly is attached to the train wheel bridge with a c-clip, the pivot for that wheel pointing straight up at camera. I’m sure this system is a cheaper way to implement the automatic winding works, but it’s definitely a bit more finicky to work on than Seiko’s usual self-contained unit from this period.

Utilizing this out of the ordinary disassembly process led to a pretty great view of the gear train for those interested in layout. You’re getting to see power all the way to oscillation. Everything came off normally from here on. Of note, the click isn’t held in with a screw, it drops into a circular cutout and is held in place by tension, another design that I’m fond of and goes to show Seiko’s creativity even in seemingly mundane decisions for daily wear movements that aren’t going to be put on display with a sapphire case back. With everything out, we can inspect the base plate and all of the jewels can be pegged.

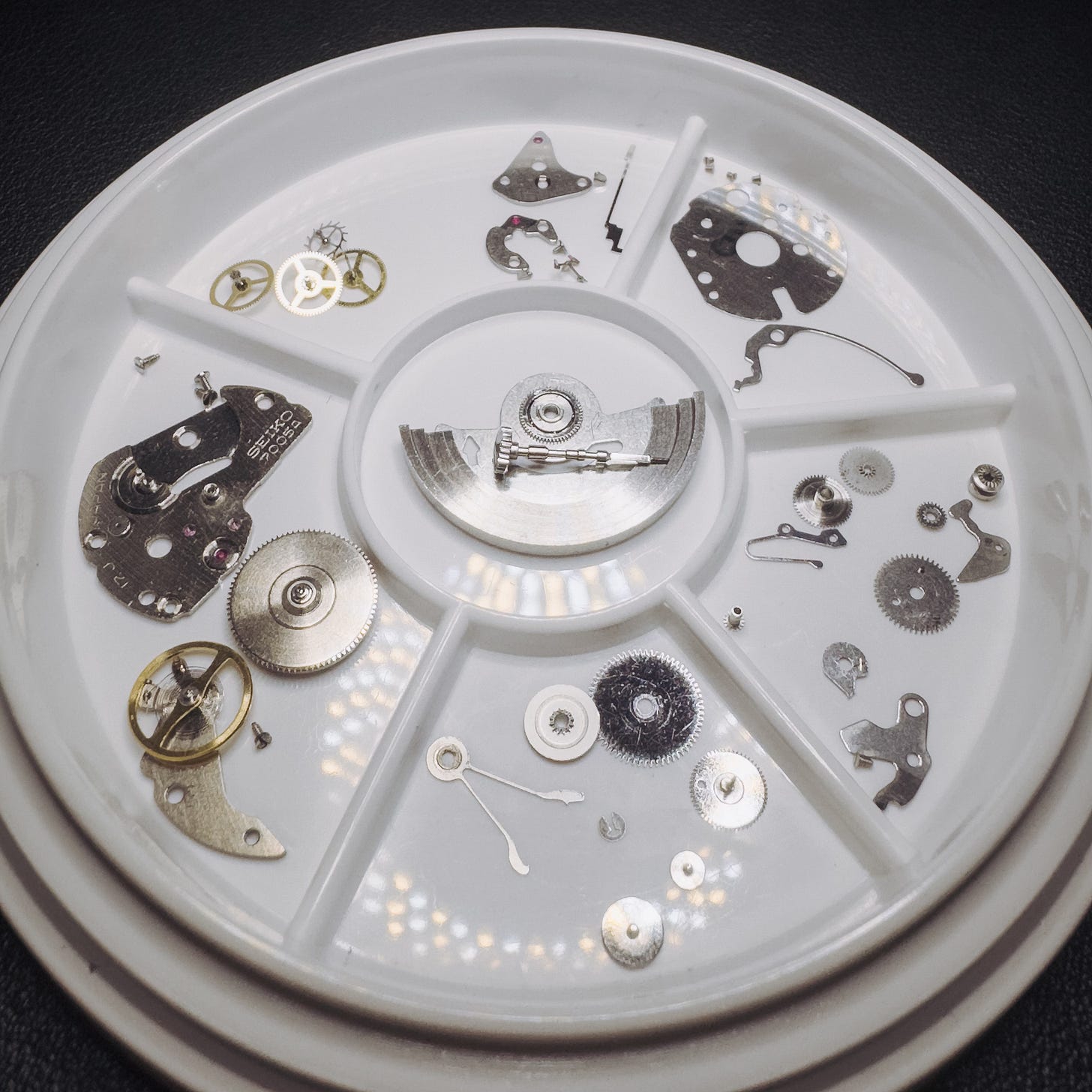

I have come to learn with today’s proliferation of YouTube watch restorers that inspection is one of the more underrated aspects of a service. I will be the first to give credit where it is due, the first time I saw someone complete this process was on YouTube. But after hundreds of videos and lots of reading on the topic, I can confidently say that inspection often isn’t given its flowers. And how could it be? A YouTube video has to hold attention, and a watchmaker sitting with their eyes to a microscope agonizing over the condition of a pivot jewel isn’t going to do that. The best creators mention that it happens, but it’s a tough thing to show in the most popular formats of learning this craft today. That’s what I do here, move my parts tray around underneath my microscope looking for anything that needs more thorough cleaning before the ultrasonic, anything that is damaged beyond expectation and needs replacing, and just generally taking in how these dozens of pieces work together in this particular format.

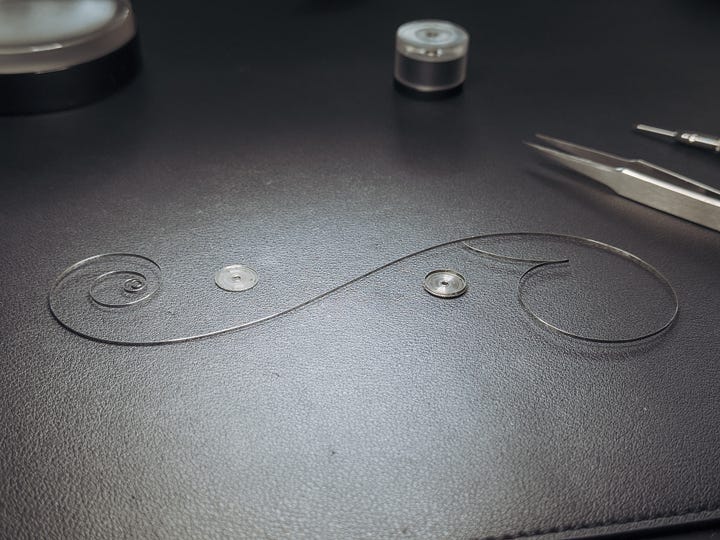

After pegging the pallet stones and some very slight adjustments to the hairspring to get a shape I am slightly more pleased with, I disassemble the barrel to find the mainspring swimming in oil. Often times par for the course unfortunately. My normal service routine involves ordering a new crystal and a new mainspring (OEM when possible) as soon as I take possession of a watch. I don’t always need them, but most times I implement them. On the rare occasion I have a watch that must be kept original to its condition when I get ahold of it, I pass along the purchased parts to the owner for servicing by the next watchmaker. In this case, as we saw earlier, the new crystal will be a non-negotiable, and after seeing how this mainspring came out, I decided it would be replaced as well.

Everything (minus balance and pallet fork) go into baskets and through the ultrasonic with some specialized solution and everything comes out looking sharp. Some braking grease on the barrel wall, a new mainspring in place, and it’s time to reassemble and lubricate.

Everything back in reverse order, with new gaskets on the stem and case, and here we have it. Timegrapher’s reading strong close amplitudes for dial up/down, we have a little variance there between dial positions and crown positions but nothing crazy for a 55 year old machine, and beat error solidly under .5ms in every position. I have it within a technical minute-per-day rate using a weighted average my preferred positions of dial up, dial down, crown down, crown left at 45° (to simulate wrist position at a keyboard), but I’ll wear it for at least a day to confirm before gifting it to lock real world measurements in.

It was a fun project, and couldn’t have been a better deal. The 7005A was a new movement for me, taught me some things, and I’m excited about the wrist action it’ll get to see from a friend in the near future.

If I decide to do another of these, I have a slew of watches that are already serviced but come with a story, and another full slate that need servicing, so subscribe to see stuff that like if it sounds like it’d float your boat.